sample

Aspiring brewers will showcase their creations at Frenchies Bistro & Brewery for a day of tastings, voting and more.

Aspiring brewers will showcase their creations at Frenchies Bistro & Brewery for a day of tastings, voting and more.  The community brewing competition returns for a second year, with the grand final set to take place on Thursday 29 August.

The community brewing competition returns for a second year, with the grand final set to take place on Thursday 29 August. As someone with a "beer-centric" palate, it is often difficult for me to find cocktails that I enjoy. When I go to a cocktail bar and order something that sounds interesting, the flavors are often overwhelmingly concentrated, and the balance tends to be either super-sweet or super-boozy. The 20-30+% ABV of most cocktails also makes them rough to drink at the same rate you would a beer...

So, I thought it would be interesting to invent a few cocktails inspired by the balance and flavors of some of my favorite beer styles. If you want to drink something that tastes exactly like a beer… drink a beer! These cocktails are “inspired” by the flavors in the style and the overall balance of the style in terms of alcohol-bitterness-sweetness, they aren’t meant to be “ringers” for drinking a given beer. I'm also trying to avoid "uncommon" ingredients... although some of these may take a little searching at a specialty grocery/liquor store or online.

I’m not an experienced bartender or mixologist, if you try one of these let me know what you think and if you have any suggestions!

Ramos Gin Fizz... Hazy IPA

Gin and Tonic is my standard cocktail order because it isn't too strong or too sweet, and the bitter/herbal notes are something I appreciate. I also find Ramos GIn Fizz to be a fun one, with the added body of an egg white and cream, and more citrus from lemon juice and orange blossom water. In this "Hazy IPA" inspired riff, I swapped out the tonic for aromatic hop water. To replace the malt sweetness and enhance the juicy flavors from the hops I added orange juice. To keep it from being too one-note orange, I added New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc, which contains high concentrations of many of the aromatics produced by Thiolized yeast and found in New Zealand hops. An egg white helps to add haze, foam, and body.

Recipe

In a shaker, combine:

1.5 oz Bombay Dry Gin

1.25 oz Orange Juice

1.25 oz Oyster Bay Sauvignon Blanc

1 Egg White

Dry shake 10 seconds

Pour into a glass, then top-up with:

6 oz Hop Water

6.7 % ABV

Ingredient Notes: The Hop Water you choose is up to you. I've enjoyed the ones from breweries as well as places like Hoplark. You can also make your own with carbonated water and some hop terpenes (I like the ones from Abstrax). Use pasteurized egg white if you are worried about the risk of salmonella. If you don't like orange, try mango or another juice that appeals to you.

Tasting Notes

Smell - Winey tropical-citrus. Slight herbal from the hops and gin. Doesn't read obviously juniper.

Appearance - Very pale, very hazy. Great sticky head.

Taste - Pleasantly sweet. Good balance of the juice and wine, without either dominating. The gin provides some depth, but again not overtly gin-y. The hop water brings herbal complexity without dominating the other ingredients with "hops."

Mouthfeel - Medium-light body, light carbonation.

Drinkability - Light and bright, citrusy.

Changes for Next Time - Certainly could add a few drops of hop terpenes if you want to send it more hoppy. Some hopped bitters could be a nice addition if you like a little more bitterness.

The Charleston... Rye Barrel English Barleywine

Thanks to Audrey, I've really come to enjoy fortified wines like Port, Sherry, and especially Madeira. It's traditionally made by halting fermentation with an addition of brandy to preserve the sweetness of the wine, then aged at elevated temperatures. The result is a like a concentrated barrel-aged English barleywine, woody, with dried fruit, and pleasant oxidative notes. I added Rye Whiskey to elevate the vanilla notes. Malta is essentially unfermented wort, but tends to have big caramel and malt extract notes from pasteurization. It helps by lowering the alcohol without thinning the cocktail, adding a little carbonation.

Recipe

Combine together:

.5 oz Bulleit Rye (95 Proof)

1 oz Broadbent 10 Year Verdelho Madeira

1 oz H&H 10 Year Sercial Madeira

Stir, then top with:

2 oz Malta India (or Malta Goya)

14.0% ABV

Ingredient Notes: Madeira comes in various sweetness levels, the really sweet ones are too sugary for my tastes in this. Sercial is the driest and Verdelho is off-dry, but find ones that work for your palate.

Tasting Notes

Smell - The vanilla/oak of the rye leads. Rich dried fruit behind it. There is some maltiness there, but definitely tastes like a really aged-out barleywine without any fresh graininess. Boozy, hotter than I'd expect from an English barleywine.

Appearance - Deep leathery brown. Good clarity. No head.

Taste - The Maderia really gives it an "aged" character, lots of raisin and date. The Sercial especially gives it a fun oxidative weirdness, and a faint acidity. There is a "sugary" sweetness, along with some alcohol warmth. Subtle bitterness.

Mouthfeel - Almost flat, "barrel sample" generously. Not quite as full as a real barleywine, but not watery or thin by any means.

Drinkability - This is one of the more evocative ones, really has a lot of the flavors you'd expect from a barrel-aged barleywine. It's a little sweet for me, but so are a lot of barleywines.

Changes for Next Time - Wish it had a little more carbonation. Otherwise it really satisfies that English Barleywine itch.

Sherry Shrub... Flemish Sour Red/Oud Bruin

One of the classic inclusions in the microbe blend for Flemish Red/Browns (e.g., Wyeast Roeselare) is Sherry Flor. This oxidative yeast forms the pellicle on sherry and produces the characteristics aldehydes that give sherry a nutty/fruity aroma. Oloroso is more "microbe" forward, funkier, while PX is more sweet and dried fruit (especially raisin). The acidity of the grapes needs a little help to mimic the classic examples of the style, so inspired by shrubs I added both vinegar and kombucha. The blend of sherries, sweetness of the kombucha, and amount of vinegar are all variables you can adjust.

Recipe

Combine together:

.5 oz Lustau Oloroso Sherry

.5 oz Lustau PX Sherry

.25 tsp Balsamic Vinegar

Stir, then top with:

3 oz Wild Bay Elderberry Kombucha

4.6% ABV

Ingredient Notes: The kombucha choice is tricky, a cherry kombucha is a nice choice if you are looking to replicate a fruited version of the style. For my palate I'd avoid those kombucha with stevia or other non-sugar sweeteners. Cream Sherry is a blend of Oloroso and PX and could be a stand-alone replacement (although you the flexibility or tweaking your blend).

Tasting Notes

Smell - Fun mix of red fruit and raisins. A little oak/almond. The elderberry works well compared to some other kombuchas since it isn't as distinct as cherry, strawberry et al. I like the Wild Bay since it doesn't have stevia or other non-sugar sweeteners.

Appearance - Clear, more amber than red. Color is about right. Not much foam.

Taste - Pleasantly sweet. Tart, with just a touch of vinegar. It has a good blend of fresh and dried fruit flavors, plum, fig, raisin etc. A little oaky. Has that classic Belgian Red balance with sugar balancing the acid.

Mouthfeel - Medium body, pleasant low carbonation.

Drinkability - This is a super interesting result for low ABV.

Changes for Next Time - Misses the maltiness of the real version, but it has the fruitiness, acid, oak, age. For a low ABV cocktail it really delivers, with the fermentation of the kombucha helping stretch the Sherry.

Espresso Martini... Coffee Stout

Flavored beers are one of the "easiest" points of entry since they already have big flavors that aren't from malt, hops, or yeast. That said, it seemed like a waste of time to make a smoothie sour cocktail. Coffee stout is still a stout, and seemed like a nice place to work in bourbon since it usually includes some barley and brings big oak aromatics that work well in stouts. A little Malta again provides body, sweetness, and a touch of carbonation.

Recipe

Combine together:

4 oz Cold Brew Coffee

1 oz Kahlua

1 oz Bourbon

Stir, then top with:

2 oz Malta India

7.5% ABV

Ingredient Notes: I should probably have sourced a "better" coffee liquor, but Kahlua is what we had on hand. Homemade cold brew would work just as well, if not better.

Tasting Notes

Smell - Big coffee nose, with some vanilla. It reads caramel malty, but not roasty.

Appearance - Deep brown, with red at the edges when held to the light.

Taste - Has a pleasant sweetness, certainly sweeter than a typical coffee stout thanks to the simple sugars. Nice note of bourbon woody/vanilla in the finish

Mouthfeel - Medium body, light carbonation.

Drinkability - I really like this one, more coffee-focused than a stout usually is, but the other notes round it out.

Changes for Next Time - I think this one straddles the line between traditional coffee stout and pastry stout. A little sugary compared to a classic stout.

Conclusion

This has been fun for me to work on the last couple months. I'll probably make a Part #2 if there is interest... already playing around with a West Coast Grapefruit IPA, Pastry Stout plus plans for Wit, Rauchbier, and Saison!

Shoot me a line if you try any of these out, or if you have suggestions or other ideas!

On Sunday 28 July, the brewery will showcase a limited-release brew at an event that celebrates sustainable practices in the industry.

On Sunday 28 July, the brewery will showcase a limited-release brew at an event that celebrates sustainable practices in the industry.  This week I cover the topic of osmotic shock in yeast, and how it can impact the fermentation performance of very high gravity beers, meads, wines, and concentrated seltzers. Osmotic Shock in Yeast Cells I had never heard of the term osmotic shock until I started making very high gravity meads. Some of my large […]

This week I cover the topic of osmotic shock in yeast, and how it can impact the fermentation performance of very high gravity beers, meads, wines, and concentrated seltzers. Osmotic Shock in Yeast Cells I had never heard of the term osmotic shock until I started making very high gravity meads. Some of my large […]  Breweries from across the country are celebrating the annual Australian hop harvest with hop festivals and fresh brews.

Breweries from across the country are celebrating the annual Australian hop harvest with hop festivals and fresh brews. In addition to music venues, bodacious barbecue, and epic tacos, this booming metropolis is The Lone Star State’s leading locale for incredible craft beer.

The post Three Beer-Filled Days in Austin, Texas appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Visiting Denver for the Great American Beer Festival (GABF) tops the bucket list of many beer lovers around the world.

The post 10 Reasons to Attend the Great American Beer Festival appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Here are five small breweries that have opened since 2020. If you haven’t heard about them yet, it’s likely you will soon.

The post Five Young Breweries You’ll Be Hearing About Soon appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

The connection between the craft beer world and ski culture is undeniable. A good beer is often a perfect way to cap a day on the slopes.

The post A Beer & Ski Lover’s Guide appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Part of my routine is to scroll through Untappd to see if I can spot any common threads to the compliments or complaints... but I don't put a huge amount of stock in the average score (see this post). Blind rating by a skilled tasting panel is the gold standard... but having a large/diverse group of beer drinkers give you feedback has value as well! With four years of Untappd scores for our IPAs at my disposal, I thought it would be interesting to see which hops "the beer drinking public" preferred in Sapwood Cellars IPAs and DIPAs!

We started this series of IPAs when we opened to showcase our favorite hop varieties. We recently released #22 (Citra-Motueka). All of the batches were 6.5-7.5% ABV, with similar malt bills (American pale barley, chit, wheat, and oats), fermented with an English-leaning yeast, and dry-hopped post-crash at 3-4 lbs/bbl. The table below is the average Untappd score of all batches dry hopped with the variety listed.

The table below include all 65 "big batch" IPAs and DIPAs we've released that don't contain adjuncts (although I did include Phantasm beers). These are diverse in terms of recipe construction, alcohol strength, and dry hopping rate. As a result, the scores are a bit more prone to bias compared to the Cheater Hops data set.

For some batches you'd expect to see a high rating due to pairing two great hops together (e.g., Nelson/Galaxy or Mosaic/Citra). Both varieties score well across all our beers, so no surprise combing them results in a well-rated IPA. More interesting is sorting by the average standard deviation for the hops included. This shows which combinations rated higher than expected given the average scores for those hops across all beers. Snip Snap (Citra/Galaxy), Cheater Hops #22 (Citra/Motueka), Shard Blade (Mosaic/Galaxy), Cheater Hops #13 (Mosaic/Simcoe), and The Dragon (Nelson Sauvin/Mosaic/Hallertau Blanc) were all in the top-10 "overachievers." These hop blends follow different approaches either "leaning into" a particular flavor (fruity, or winey) or balancing fruity with a danker variety.

Rounding out the top-10 are two all-Simcoe (Cheater Hops #12 and Drenched in Green), two all-Mosaic (Fundle Bundle and TDH Trial #1), and an all-Nelson beer (3S4MP). Certainly a sign that these hops can shine alone compared to Citra and Motueka which are highly rated in blends, but haven't exceled in single-hop beers (despite our best efforts). Of course you need a great lot of hops for this to work; the bottom-10 also includes single-hop beers featuring: Simcoe (Cheater Hops #9), Nelson Sauvin (Cheater Hops #11), and Mosaic (Fumble Bumble)!

Two beers with Galaxy and Nelson (Cheater X and X2) each had a standard deviation close to 0. They still rate well, but no better or worse than expected across all beers with Nelson or Galaxy.

Surprisingly three of the bottom four included three varieties Cheater Hops #7 (Simcoe, Citra, Mosaic) Cheater Hops #6 (Motueka, Mosaic, Simcoe) False Peak (Idaho 7, Sultana, Citra). Blending hops can create a generic "hoppiness." These beers may have been missing a distinct "wow" aroma for people to grab onto.

The high/low scores for different batches brewed with the same single hop variety really drives home how unreliable this data likely is. Without multiple batches hopped with the same hop combination, it is impossible to say with certainty if a beer scored well because of aromatic synergy or a delicious lot of hops. Luckily several of the top-rated combinations are beers we have brewed multiple times.

The data does suggest to me that using one or two varieties for the dry hop is the best bet for making the most appealing IPA unless you have something very specific in mind. Often when breweries use a large number of hop varieties in a beer it is to promote consistency (batch-to-batch and year-to-year). It would be interesting to expand the data set to include beers from other breweries. That would produce data that is less specific to our particular brewing approach, hop sourcing, and customers' palates.

When it comes to brewing delicious beer, there are few aspects more important than the yeast. A healthy fermentation allows the malt, hops, and adjuncts to shine. Pitching the right amount of healthy cells helps ensure that the finished beer has the intended alcohol, expected residual sweetness, and appropriate yeast character.

Over the last four years at Sapwood Cellars we've slowly improved our yeast handling. We've noticed improved fermentation consistency, and better tasting beers. Most of our process is excessive for a homebrewer, but it might give you some ideas!

Harvesting Yeast

We harvest yeast from moderate gravity beers when possible as these cells are less stressed and healthier as a result. Our general rhythm is to brew a pale ale with a fresh pitch, and harvest from that tank for an IPA and DIPA the following week. Once the pale ale fermentation is complete (repeated gravity readings, and no diacetyl or acetaldehyde sensory) we can and soft-crash to 56-58F (13-14C). Cold and dissolved CO2 encourage the yeast to settle out. Specific temperature and time are strain and tank dependent, but that works for most of the English-leaning strains we use (Boddington's, Conan, Whitbread, and the Thiolized-variants).

Once the beer has been cold for 24 hours, we attach a 1/2 bbl brink to the bottom of the tank and pasteurize through the line and brink with 180F (82C) water from our on-demand. 25 minutes hot ensures there aren't any stray microbes that will be passed onto the subsequent batches. After pushing out the water with CO2 pressure we spray the brink with cold water then pressurize it and the tank to ~10 PSI.

We then dump about a gallon (4L) from the T until the yeast looks good (creamy, off-white) and then begin collecting into the brink. You don't need to dump a large volume of yeast. By keeping steady pressure on the tank and slowly releasing pressure on the brink through the valve at the top we ensure that the yeast won't come out of the cone too quickly (which could punch through pulling in more beer than yeast) and won't foam up in the brink. It takes 10-15 minutes to fill the brink. Usually we are able to collect 110-130 lbs (50-60 kg) before yeast starts coming out the top of the brink.

We collect yeast before dry hopping to avoid having hops mixed in with the yeast. We also prefer the "less rough" flavor we achieve by dry hopping cold. If you dry hop early-mid fermentation and want to harvest, drop as much of the hops out as you can before crashing and harvesting.

Yeast Storage

Whenever possible we pitch within 72 hours of harvest. Larger yeast cultures generate more heat and thus tend to lose viability more rapidly. Store the yeast as cold as possible, which for us is ~36F (2C) in our walk-in. Ideally that would be closer to 32F (0C) to further slow its metabolism. Shake twice a day to dissipate hot-spots and vent down the pressure to knock-out CO2. If storing the yeast for more than a few days, attach a blow-off line to prevent pressure from building.

There are studies about various additives for maintaining high yeast viability. We've added phosphate buffer to prevent a drastic pH drop. It's difficult to tell from a single data point, but viability dropped from 95% to 89% after a week of storage. We've seen closer to 10% reductions the handful of times we've stored yeast that long previously.

We generally won't harvest and repitch beyond three generations (although recently we went to five). That's because with our limited number of tanks, variety of yeast strains, and canning schedule we'd eventually have to hold onto yeast for a couple of weeks before pitching or harvest from a strong beer.

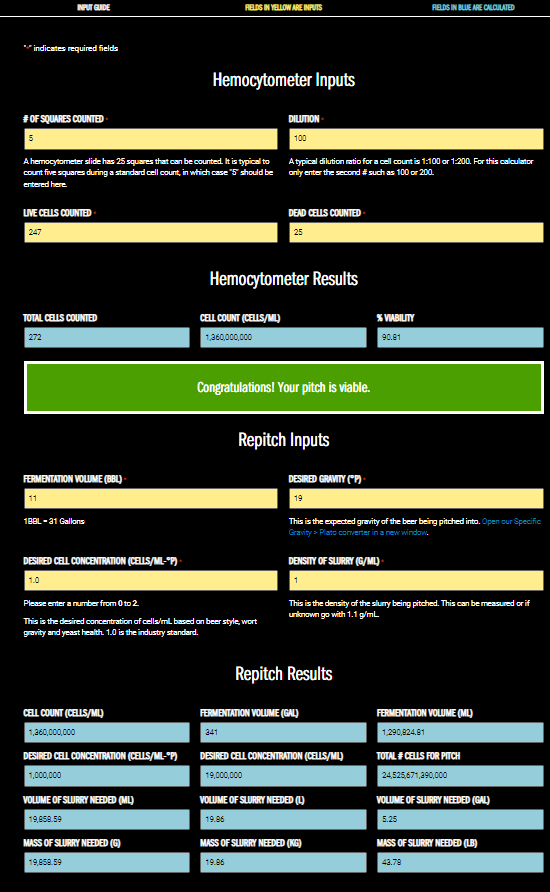

Determining Cell Count and Viability

There are plenty of successful brewers who pitch a standard weight by barrel/gravity, but knowing how many live cells you actually have is a great way to improve consistency. It's especially valuable if you use a variety of strains or want to bring in a new strain. Our harvests of the same strain can vary by as much as three times in terms of live cells per g of slurry (~.5-1.5 billion cells). The cost of all of the equipment required is ~$500, less than a single commercial 10 bbl yeast pitch from some labs.

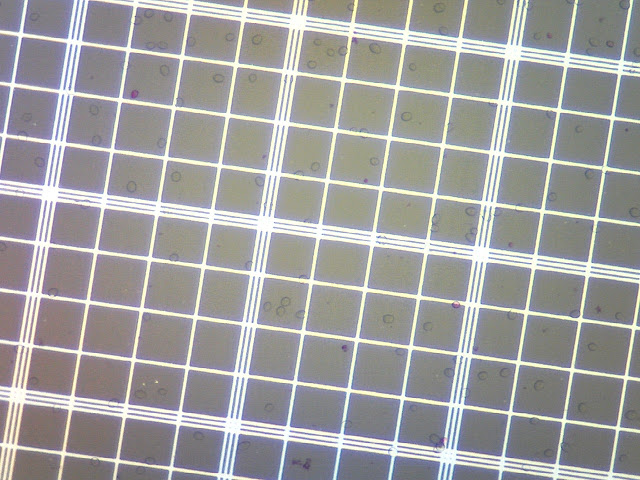

Start by shaking the brink to homogenize the culture. Then run a cup of yeast out, dump it (to avoid counting the cells packed around the port) and then pull a sample. The next step is to dilute the culture to a "workable" concentration - 1:100 for us. Too many cells packed together makes for a culture that is impossible/laborious to count, while too few raises the chances luck will throw-off the count. For a long time I diluted by volume, performing two sequential 10X dilutions with a micropipette. This had two drawbacks. First getting an accurate volume of yeast slurry is tricky because it is foamy and has small bits of trub that can plug-up the pipette. Second, we pitch by weight, so there was always some estimation when it came to converting the volume to a weight or the extra step of determining the physical density of the slurry by mixing with water in a graduated cylinder on a scale. What we do now is dilute by weight, which gives us cells per gram rather than cells per milliliter.

Our scale is accurate to .2 g, so weighing 1 g of yeast into 99 g of water has a ~20% margin of error. As a result I do 490 g of water with 5 g of the yeast slurry. This reduces the maximum margin of error to ~4%. After pouring the diluted culture back and forth to mix, I take 9.9 mL of the diluted culture with the micropipette and add .1 mL of a stock dye solution of Erythrosin B and phosphate buffer (1 g in 50mL of buffer). This results in a total dilution of 100X. You could go even further, a 10X dilution by weight (50 g yeast with 450 g of water) followed by a 10X dilution by volume (1 mL of the diluted culture with 8.9 mL water and .1 g of dye). Live cells are able to expel the Erythrosin B so they won't be stained, meaning any red yeast cells are dead. You can use a variety of other stains, but Erythrosin B is a food coloring and much safer to handle than methylene blue or trypan blue. Here's a post from Escarpmant Labs on using it inspired by my Tweet (which was in turn inspired by this).

Luckily the Boddingtons-type strain we use for most of our batches isn't "excessively" flocculent. When we fermented a run with Whitbread we ran into issues with the cells being too clumpy to count. Luckily BrewKaiser has a whole post on additions you can add to help. Phosphoric acid worked OK, but a local brewer suggested disodium EDTA, which I plan to buy before we do another run with a similar strain.

Next, place a couple drops on the diluted culture a hemocytometer, apply the slide cover, and stick it under a microscope (we have an Omax). Count the live and dead cells in five squares (each made up of 25 small squares) - four corners, and center. This provides a large enough sample size to avoid undue randomness. A small tally counter helps keep track. The standard rule is to count cells touching the left and top lines, but not the right or bottom. Count connected cells as two only if the daughter cell is more than half the size of the mother. Then I plug the totals into Inland Island's Yeast Cell Count Calculator. Usually our harvests are 80-90% viable off a fresh pitch, and they tend to go up from there on subsequent generations (90-95%). If your viability isn't great it could either be that the yeast isn't getting enough nutrients/oxygen, your initial pitching rate was too high or low, or that you are waiting too long to harvest.

There are automated solutions for yeast counting, but with some practice the whole processes will take less than 10 minutes.

Pitching YeastTo pitch, we attach the brink to a T inline during knock-out. With the brink on a scale we use CO2 to slowly push in the desired weight of yeast (calculated based on the cell count, wort gravity, and volume). We pitch during knock-out so the yeast mixes with the aerated wort as it goes into the fermentor. White Labs advocates using a pump to pitch their fresh yeast inline to achieve better mixing with the wort. Best practice is to do another cell count off the tank once knock-out is complete to validate your process (we did it a few times, but now trust our approach).

When we started brewing more double batches to fill our 20 bbl tanks, we were pitching enough cells for 20 bbls along with the first 10 bbls of wort. Our thought process was that the yeast wouldn't do much in the 3-4 hours before the second half of the wort went in. However, we found our fermentations were less reliable, often dragging towards terminal gravity, and the yeast from those batches had much lower viability than expected. Both of these issues improved significantly once we switched to pitching only enough cells for the initial knock-out volume. This allows for more growth and thus a higher proportion of younger yeast cells.

Hopefully this overview of our process is helpful for someone starting a new craft brewery, or looking to take their yeast management to the next level. As with anything in brewing, the more variables you can track and control the more consistency you'll have in your results. Yeast management isn't a "fun" topic, but it is one of the simplest things a brewery can do to increase consistency, improve flavor, and save money!

Architect and author Neil Ginty talks about some of his favorite breweries that give you a front row seat to the brewing process.

The post Form & Function: Brewery Visits with an Architect appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

This week I take a look at the very important topic of blending traditional sour and barrel aged beers. Traditional sour beer brewing, where fermentation is done before the souring, as well as many barrel aged beers can be hard to get right the first time. Both involve very long maturation cycles, relatively high alcohol […]

This week I take a look at the very important topic of blending traditional sour and barrel aged beers. Traditional sour beer brewing, where fermentation is done before the souring, as well as many barrel aged beers can be hard to get right the first time. Both involve very long maturation cycles, relatively high alcohol […]  This week I take a look at the Dunkles Bock beer style from Northern Germany and examine its history and how to brew one. Dunkles Bock is a dark, strong, malty German lager. Dunkles Bock History Bock beer traces its history to Einbeck, a small German town between Kassel and Hannover. Brewing records mentioning bock […]

This week I take a look at the Dunkles Bock beer style from Northern Germany and examine its history and how to brew one. Dunkles Bock is a dark, strong, malty German lager. Dunkles Bock History Bock beer traces its history to Einbeck, a small German town between Kassel and Hannover. Brewing records mentioning bock […] The roots of American craft beer extend throughout the nation, but the bines of the movement are clearly embedded in the Pacific Northwest.

The post 5 Pacific Northwest Breweries to Please Any Palate appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Fairbanks, Alaska, attracts visitors hoping to capture sight of the aurora borealis. If you're hunting aurora, these Fairbanks craft breweries should be part of your adventure.

The post Aurora Hunting and Craft Beering in Fairbanks, Alaska appeared first on CraftBeer.com.