ingredients

COVID prompts Australian to relinquish chair of judging role at International Brewing Awards.

The post Bill Taylor steps aside from world beer awards appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

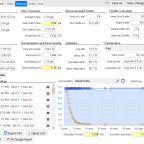

This week I cover some of the basic concepts of using fruit in BeerSmith for making beer, wine, cider or meads. Fruit Basics BeerSmith 3 supports the use of fruit juice, purees, honey and whole fruits natively when making beer, mead, wine and cider recipes. Typically most fruits are added during primary or secondary fermentation. […]

This week I cover some of the basic concepts of using fruit in BeerSmith for making beer, wine, cider or meads. Fruit Basics BeerSmith 3 supports the use of fruit juice, purees, honey and whole fruits natively when making beer, mead, wine and cider recipes. Typically most fruits are added during primary or secondary fermentation. […]  This week I take a look at one of those little known features in BeerSmith brewing software that can make building recipes just a little easier. This feature is available in the desktop, mobile and web based versions of BeerSmith. What is “Save as Default”? When you build a recipe in BeerSmith from scratch you […]

This week I take a look at one of those little known features in BeerSmith brewing software that can make building recipes just a little easier. This feature is available in the desktop, mobile and web based versions of BeerSmith. What is “Save as Default”? When you build a recipe in BeerSmith from scratch you […] From a stout to a Saison with a twist, these are our top Spring beers.

The post Spring’s 16 outstanding Australian craft beers appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

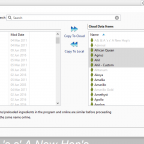

This week I take a look at how to exchange profiles and ingredients between the desktop version of BeerSmith and the web based version. These features were added as part of the BeerSmith 3.2 release and BeerSmith Web release. These features are also covered in a video tutorial on web based profiles and ingredients here. […]

This week I take a look at how to exchange profiles and ingredients between the desktop version of BeerSmith and the web based version. These features were added as part of the BeerSmith 3.2 release and BeerSmith Web release. These features are also covered in a video tutorial on web based profiles and ingredients here. […] New beer designed to pair with the restaurant group’s contemporary Chinese dishes.

The post Lotus Dining and White Bay team up on rice lager appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Brewery is in the midst of a multi-stage expansion across all areas of operations.

The post Burleigh toast 15 years with expansion and a new beer appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

This week I take a look at the various versions and options available for using BeerSmith to develop your beer, mead, wine and cider recipes. This list is current as of mid 2021 following the release of BeerSmith 3.2 desktop and BeerSmith Web. BeerSmith Versions and Platforms BeerSmith Desktop – The BeerSmith desktop program, currently […]

This week I take a look at the various versions and options available for using BeerSmith to develop your beer, mead, wine and cider recipes. This list is current as of mid 2021 following the release of BeerSmith 3.2 desktop and BeerSmith Web. BeerSmith Versions and Platforms BeerSmith Desktop – The BeerSmith desktop program, currently […]  An overview of how you can use preloaded and custom ingredients and profiles in the BeerSmith Web recipe builder as well as how to transfer ingredients and profiles from your existing BeerSmith desktop program. Related Videos: Creating Equipment Profiles | Recipe Design Tab | Recipe Adjustment Tools | BeerSmith Web Overview | Find/Scale Recipes | […]

An overview of how you can use preloaded and custom ingredients and profiles in the BeerSmith Web recipe builder as well as how to transfer ingredients and profiles from your existing BeerSmith desktop program. Related Videos: Creating Equipment Profiles | Recipe Design Tab | Recipe Adjustment Tools | BeerSmith Web Overview | Find/Scale Recipes | […]  This week I take a look at homebrewing in the modern era, how it has developed and the impact of technology on brewing. A Quick History of Modern Homebrewing While brewing beer at home has been done for many thousands of years, the modern history of homebrewing in the US has some clearly defined dates: […]

This week I take a look at homebrewing in the modern era, how it has developed and the impact of technology on brewing. A Quick History of Modern Homebrewing While brewing beer at home has been done for many thousands of years, the modern history of homebrewing in the US has some clearly defined dates: […] Non-alcoholic craft brewery to ‘raise their goals’ after snaring Amazon grant

The post UpFlow to chase export markets after $200K win appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

A detailed overview of the capabilities of our BeerSmith Web recipe editor which supports beer, wine, mead and cider recipes. The same capabilities are available on the desktop version of BeerSmith. Related Videos: Building a Recipe | The Design Tab | Find/Scale Recipes | Profiles and Ingredients | Pro Recipe Tips | All Videos

A detailed overview of the capabilities of our BeerSmith Web recipe editor which supports beer, wine, mead and cider recipes. The same capabilities are available on the desktop version of BeerSmith. Related Videos: Building a Recipe | The Design Tab | Find/Scale Recipes | Profiles and Ingredients | Pro Recipe Tips | All Videos  I’m pleased to announce the release of a web based version of BeerSmith 3 along with a desktop BeerSmith 3.2 update. The web based version allows you to edit your cloud based recipes from anywhere by simply logging into your cloud account at BeerSmithRecipes.com. BeerSmith Web Highlights Web based recipe editing from any browser by […]

I’m pleased to announce the release of a web based version of BeerSmith 3 along with a desktop BeerSmith 3.2 update. The web based version allows you to edit your cloud based recipes from anywhere by simply logging into your cloud account at BeerSmithRecipes.com. BeerSmith Web Highlights Web based recipe editing from any browser by […]  This week I wanted to share a more detailed look at the upcoming Web based version of BeerSmith which is scheduled for release in June of 2021. It will be available to all Gold+ license holders of BeerSmith 3. When released, you can simply log into your existing BeerSmithRecipes.com account and edit recipes in your […]

This week I wanted to share a more detailed look at the upcoming Web based version of BeerSmith which is scheduled for release in June of 2021. It will be available to all Gold+ license holders of BeerSmith 3. When released, you can simply log into your existing BeerSmithRecipes.com account and edit recipes in your […] This year’s Little Home Brewers challenge looks to reimagine Oktoberfest.

The post Little Creatures home brew competition returns appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Sydney locals combine their love of beer and bowling by releasing the Bowlo Draught.

The post New beer aims to help keep the local bowlo alive appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Beer historian Martyn Cornell joins me this week to discuss the history of English Mild Ale which was the dominant UK beer style for nearly 80 years. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. […]

Beer historian Martyn Cornell joins me this week to discuss the history of English Mild Ale which was the dominant UK beer style for nearly 80 years. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. […] Tasmania’s Van Dieman Brewing is holding its annual hop picking day this Saturday.

The post Get a hands on approach to making beer appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Sydney Brewery’s Pilsner wins best in show at Queensland’s top beer awards.

The post The secret to the success of the quiet achievers appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Alcohol free beer is flowing in venues as Australia’s first NA bar opens soon.

The post The heaps normal growth of on-premise NA beer sales appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Growth in sales is attributed to people buying local and drinking less but better.

The post COVID-19 accelerates off-premise craft cider sales appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Dr Charlie Bamforth joins me this week to discuss foam and head retention in beer. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does not support the audio element. Topics in This Week’s […]

Dr Charlie Bamforth joins me this week to discuss foam and head retention in beer. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does not support the audio element. Topics in This Week’s […] The team behind well-known Sydney brewery to open a brewpub in country NSW.

The post Nomad go overland with new Mudgee brewery appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

I felt it was time to bring you up to date on some of the new things happening at BeerSmith. BeerSmith Web Version I’ve been working hard to build a complete web based version of BeerSmith 3. Last year I released most of the BeerSmith tools to Gold+ members on the BeerSmithRecipes.com web site along […]

I felt it was time to bring you up to date on some of the new things happening at BeerSmith. BeerSmith Web Version I’ve been working hard to build a complete web based version of BeerSmith 3. Last year I released most of the BeerSmith tools to Gold+ members on the BeerSmithRecipes.com web site along […] Go behind the Counter Culture series with their head brewer and innovation manager.

The post Stone & Wood’s 10 week cycle of ‘fresh air’ appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

This week I cover mead making fermentation and finishing. Last week in part 1, I provided an overview of mead making and the first steps of making the must, pitching your yeast and adding nutrients. This week I will cover the remaining steps. As I covered last week the key components of modern mead making […]

This week I cover mead making fermentation and finishing. Last week in part 1, I provided an overview of mead making and the first steps of making the must, pitching your yeast and adding nutrients. This week I will cover the remaining steps. As I covered last week the key components of modern mead making […] Brewpubs boost flavor on their menus by pouring their beers into the pizza dough and serving up the perfect slice.

The post Beer-infused Pizza Dough is a Perfect Brewpub Pairing appeared first on CraftBeer.com.