fermented

One of the classic styles, and one of the most fabulous beers steeped in history, Kölsch is often underrated and overlooked.

One of the classic styles, and one of the most fabulous beers steeped in history, Kölsch is often underrated and overlooked.  John Palmer guides you through brewing this delightful beer, that is widely praised but far too often poorly replicated.

John Palmer guides you through brewing this delightful beer, that is widely praised but far too often poorly replicated.  John Palmer guides you through brewing this delightful beer, that is widely praised but far too often poorly replicated.

John Palmer guides you through brewing this delightful beer, that is widely praised but far too often poorly replicated. Ice cream soda floated into our collective consciousness 150 years ago. Now, a beery take on this fanciful beverage is winning converts.

The post A Dreamy Pairing: Beer & Ice Cream appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

With spring well and truly sprung, we highlight three new fruit beer releases as we reach ideal weather for the style.

With spring well and truly sprung, we highlight three new fruit beer releases as we reach ideal weather for the style.  From Irish stout to hazy pale ales, Beer & Brewer rounds up the best non-alcoholic beers for Dry July.

From Irish stout to hazy pale ales, Beer & Brewer rounds up the best non-alcoholic beers for Dry July.  Capital Brewing Co has announced that it has bought one of Australia’s most renowned cider brands, Batlow Cider.

Capital Brewing Co has announced that it has bought one of Australia’s most renowned cider brands, Batlow Cider. While I love the pure expression of malt, water, hops, microbes, barrel, and time... fruit can make a fantastic addition to a barrel-aged sour. From a "sales" standpoint it is also easier to explain the difference between beers with fruit, than those with subtle differences in grain bill or microbes. Most people know they like cherries, plums, and raspberries... they may not know they enjoy horse blanket, minerality, or rubbery notes.

This is the third in a series of posts updating my thoughts from American Sour Beers ten years ago. The two beers featured below (Jammiest Bit and Fruit of Many Uses) were both part of the first shipment of the Sapwood Cellars Out of State Shipping Club. Memberships for that shipment are closed, but you can still sign-up now for the next shipment fall 2024 ($146/shipment including shipping). Bottles of both are still available at the tasting room!

Sourcing Fruit

I would almost always rather use fresh in-season local fruit over a puree, juice, freeze-dried, concentrate, and especially natural extract. Local produce tastes unique, meaning a beer that doesn't taste the same as one brewed on the other side of the country or by a larger brewery. You'll get a more complex character from having beer in contact with the stems, skins, pits etc. Working with farms, orchards, and vineyards "fits" the narrative of an artisanal product... making it look good on social media too! Not to mention our fruiting tanks (without conical and glycol jackets) work best with whole fruit rather than purees.

Talking directly to farms and orchards at farmer's markets is a great place to start. Tasting things, chatting about what sort of capacity (and excess) they might have. Sometimes you can get a good deal on seconds... but for me these often aren't worth it since it can take a lot of time and effort to sort them (going rotten before they are all ripe) and cut-out mold etc.

We've used IQF (Individual Quick Frozen) fruits several times with great results. For smaller batches I've just gone to supermarkets, found a product I like the flavor of... and bought out a couple locations. Online specialty purveyors like Northwest Wild Foods have weird things you might not find locally, like honeyberries. For lager batches we've ordered from Coloma Frozen Foods, but don't do it regularly as refrigerated shipping is expensive. Recently we've been getting our raspberries from Twin Springs Fruit Farm (which freezes their own). Using high-quality frozen fruit is something great lambic breweries do, and it allows to extend the fruiting season so you don't have to have enough tanks for all of your fruit beer at once!

That said, not all fruits are available locally. You can certainly source whole fruits from a good local produce supplier (and we have), but purees have their place too... especially in "smoothie" type sour beers. That said, there is no magic bullet on sourcing them. We've used Oregon Fruit, Greenwood Associates, Kerr/Ingredion, Asceptic Fruit Purees, Hop Havoc, Boiron, FruitGuild, and Araza. None of them are "always good" and none of them are always bad. It's often about preference. For example, Oregon Pineapple is thin, closer to juice, great for an IPA where you'll drop out the solids. Araza Pineapple is much thicker, perfect for a smoothie sour. Both taste great.

Frozen wine grapes are another great option, either juice or must. Again, I love working with local vineyards (Crow Vineyard and Winery has been especially nice to work with), but that isn't always an option! We've had good luck with Grapes for Wine and Wine Grapes Direct.

The only concentrates I've enjoyed are "freeze" concentrates (the wild blueberry and raspberry from Greenwood Associates are great). I've disliked the flavor of all of the standard high-concentration "boiled" concentrates which end up tasting like caramel, and are so thick that they are difficult to mix with beer. Granted, after an early batch with concentrates from Kerr we really haven't tried any more. On the other hand, Kerr's NFC (Not From Concentrate) raspberry juice was terrific, so I suspect the issue was the concentration.

Freeze-dried fruit can be a pretty good option for tropical fruits like mango. I've yet to find a mango puree that didn't taste cooked. The freeze-dried stuff tends to have a brighter "mango popsicle" flavor. It can be pricy, but there is a lot of flavor pound-for-pound. North Bay Trading generally seems to have the best bulk pricing.

Processing

We have a chest freezer at the brewery so we can keg fruit when it is ready, but not necessarily have to go onto it immediately. Freezing the fruit also helps break the cell walls allowing better/quicker contact and refermentation. Just make sure to line your freezer with cardboard so the bags don't stick to the interior. That's all we do for berries. Freeze them, let them thaw in the tank, then transfer beer on the next day.

When it comes to larger fruits (e.g., stone fruit like peaches and nectarines) we'll manually quarter them and discard the seeds/pits. In an ideal world we'd selectively process and freeze the fruit on a flow basis as it reached peak ripeness.

I've never had good luck with fermented citrus, so for limes, lemons, oranges, and grapefruit we use the zest. We use a Starfrit Electric Rotato Express. It struggles a bit on really large grapefruits, and we go through a couple a year as they just aren't sturdy enough for a "production" environment.

There is some science that cherry stems have glycosides that Brett can work on to free fruity aromatics... but in practice I find they add a "stemmy" flavor that reminds me of dried leaves. I like the pits though. Obviously nice to find a source that has your preferred processing so you don't have to do it!

However you process the fruit, purge the tank with CO2 thoroughly before transferring beer in. This will help ensure the brightest, freshest, fruit expression possible!

Reyeasting

We usually repitch rehydrated (with StartUp/GoFerm) wine yeast along with the fruit to ensure a rapid refermentation, scavenge oxygen, and enhance the fruit character. While our sour beer production area has "light" HVAC, we don't have jackets for our fruiting totes (Flextanks). As a result, we'll change our yeast depending on the seasonal temperature. Usually using more heat-tolerant red wine strains in the summer, and cool-loving whites in the winter.

We also add a small amount (5-7 PPM) of hop extract to prevent additional acidification if the beer is already sour enough for our tastes. See my article on hopping sours for more details.

Fruit Contact Time

I've slowly come to be an advocate for relatively short contact time, enough to ferment out the sugars, but not much more. This is especially true of raspberries (which develop a "seedy" flavor from extended contact). I've also heard strawberries as a quick-contact to reduce the phenolic "plastic" flavor they can develop. Although I've also read that can be varietal specific, and others claim freeze-drying can help mitigate.

If I'm aging a beer on raspberries and another fruit that I prefer longer contact, I'll do that separately in two totes. That way we can keg off the raspberry after 10-14 days, while the cherries, wine grapes etc. have a little more contact time (1-2 months). They we blend them together. This could also be accomplished sequentially by racking the beer off of the raspberries and then onto the cherries.

Separating Fruit and Beer

Our Flextanks have stainless steel filters from Utah Biodiesel Supply fitted over the racking arms with stoppers. A false bottom would likely work even better, but with a slow transfer we haven't had many issues with whole/pieces of fruit. The lone one I remember causing havoc with chunks of frozen mango that totally disintegrated.

Second Use Fruit

With all the time and effort of getting the fruit and processing it, we often try to get a second beer out of it. Second use fruit is more subtle, allowing a more "beer-forward" balance. You could likely get similar results from ~25% of the fruiting rate, but second use fruit is easier (and free)!

We'll often just push in a single keg of sour beer onto the fruit from a whole batch to "rinse" it. This gets a big fruit character and it's an easy way to make a unique one-off

We'll do a whole new batch onto especially high fruiting rate beers. For example when we did 4 lbs/gal of raspberries in Throwing Hearts with Other Half, we went onto the fruit with a sour red along with vanilla beans to make Galactic Swirl.

For Fruit of Many Uses, we racked the beer sequentially into each tote after a previous beer. Getting Chardonnay grapes (from Field Learning, our Bissell Brothers collab) before going into barrel, followed by raspberries, then cherries (both from Jammiest Bit), and white nectarines (Polite Company).

We haven't tried it, but I know some brewers who will knock-out fresh wort onto spent fruit as a way to get fruit flavor along with a strong house culture.

No matter your technique, be extra mindful of limiting oxygen exposure as you won't have refermentation to scavenge oxygen.

Jammiest Bit

Barrel #71 Golden Strong #3 (Pils, 2-row, Chit, Wheat malt, and Flaked Wheat to 1.056 with aged Celia and Lemondrop pellets). Primary fermentation with 58W3 and some microbes from a blend of older barrels that was primarily Yeast Bay Mélange (but also various dregs from Oxbow, Jester King, and Backacre). Then aged 17 months in a second-use Malbec barrel. The culture in the barrel itself was originally derived from a De Garde bottle.

Barrel #36 Marylambic #7 (Weyermann Barke Pilsner, Flaked Wheat, and Chit to 1.044 with .5 lbs/bbl aged East Kent Goldings). Primary fermentation T58. Then aged 13 months in a third-use Pinot Noir barrel. The microbes in the oak were originally from dregs from two Floodlands bottles.

Racked into two totes one with 150 lbs Twin Springs Raspberries and the other with 150 Baugher's Orchard Sour Cherries. Both frozen and thawed. Each received 10 g of HopSteiner Alpha Extract, and fresh 71B for refermentation.

Smell - Mix of fresh berries, raspberries more than cherries. Not a hugely complex funky or "Brett-forward" beer, but there is a little lemon and hay Barrel character is hidden behind the fruit as well.

Appearance - Crystal clear, brilliant red-purple. Light-pink head fizzles quickly, but stays as a thin covering.

Taste - Cherries come through more on the palate. Good fruit intensity, still really fresh/vibrant. Firm acidity, slight sharpness from the malic acid of the cherries? Again not an especially complex or funky beer, but it’s a showcase for good fruit. The Baugher's cherries without stems seems to have been a good choice. A bit sweet which lends a more Flemish Red lean rather than Lambic or Saison.

Mouthfeel - Medium-high carbonation. Medium-light body.

Drinkability - It grows on me as I drink it and my palate gets used to the acidity. Good blend of fruit, bright flavor, I just wish the base beer was a little more interesting.

Changes for Next Time - Wouldn’t mind depitted cherries to make sure we are getting good extraction.

Fruit of Many Uses

Base Beer: Belgian Pale #3

78% Murphy & Rude Virginia Pilsner

18% Murphy & Rude Wheat Malt

4% Murphy & Rude Vienna Malt

OG 1.047

.5 lbs/bbl 5-year-old Australian Summer Hop Pellets

Primary Yeast Lalvin 71-B

Microbes from Chardonnay Grape tote (originally a Bissell Brothers house souring culture they sent for the collab).

Then aged in a third-use Cabernet Sauvignon (microbes originally from Modern Times House of Sand) and Barrel #41 fourth-use merlot barrel for 11 months (microbes in barrel included East Coast Yeast Senne Valley, Bokkereyder dregs, Mad Fermentationist Saison, Casey, and Afterthought dregs)

Racked sequentially onto 150 lbs Twin Springs Raspberries, 150 Baugher's Orchard Sour Cherries, and 250 Twin Springs White Jade Nectarines.

Smell - The berry leads, more cherry than raspberry. Earthy hay, candied fruit salad. The nectarines and grapes don’t shine in the aroma, but they help to send it in a direction that isn’t one-note “berry.” Almost apricot brandy as it warms. I don’t taste anything off from the pits, seeds etc.

Appearance - Carbonation seems a little low. A hard pour results in only a two-finger white head. A few bubbles rising through the pale body. Good clarity.

Taste - Pleasantly tart lemony acidity, without being harsh. The nectarine comes through more distinctly on the palate. Finish is berry again, but light, bright, and juicy finish. Non bitterness.

Mouthfeel - Medium carbonation, could be spritzier. Smooth, no astringency. Light body, without being thin.

Drinkability - Really complex with the different fruit notes coming in and out of awareness.

Changes for Next Time - The Chardonnay is mostly lost, would be a better feature in a plain beer or maybe light dry hopping.

A new wave of Asian American brewers is putting their heritage at the heart of their craft.

The post Redefining Craft Beer: Asian Americans Brewing Up Heritage appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

This week I dive into the very important topic of cleaning and sanitation for beer brewing and cover some of the basic terms and definitions. In part 2 I’m going to cover the cleaning process and strengths and weaknesses of different cleaners, and in part 3 I will cover sanitation and sanitizers. Why is Cleaning […]

This week I dive into the very important topic of cleaning and sanitation for beer brewing and cover some of the basic terms and definitions. In part 2 I’m going to cover the cleaning process and strengths and weaknesses of different cleaners, and in part 3 I will cover sanitation and sanitizers. Why is Cleaning […]  This week I cover the topic of osmotic shock in yeast, and how it can impact the fermentation performance of very high gravity beers, meads, wines, and concentrated seltzers. Osmotic Shock in Yeast Cells I had never heard of the term osmotic shock until I started making very high gravity meads. Some of my large […]

This week I cover the topic of osmotic shock in yeast, and how it can impact the fermentation performance of very high gravity beers, meads, wines, and concentrated seltzers. Osmotic Shock in Yeast Cells I had never heard of the term osmotic shock until I started making very high gravity meads. Some of my large […] The longer I brew mixed-fermentation beers, the more I appreciate just how important the hopping rate is. Controlling lactic acid production by inhibiting lactobacillus is hops' most well-appreciated function in sour beers. Hop compounds become more effective at inhibiting Lactobacillus as the pH drops, creating a natural "limit" on their lactic acid production. What it took me a long time to appreciate was how much hop compounds (beyond IBUs) lead to a greater expression of what I think of as classic Brett "funk."

When Scott and I began the mixed-fermentation program in 2018-2019, generally our issue was beers not souring enough. I started pulling levers (lower hopping rates, higher mash temps, less attenuative primary strains etc.) By 2020-2021, we were having excessive acid production... Most non-fruited beers were dropping to a firmly-acidic 3.1-3.3 pH, while fruited beers were often difficult to drink in quantity at 3.0-3.1 pH with some dipping to "obnoxiously acidic" high-2s.

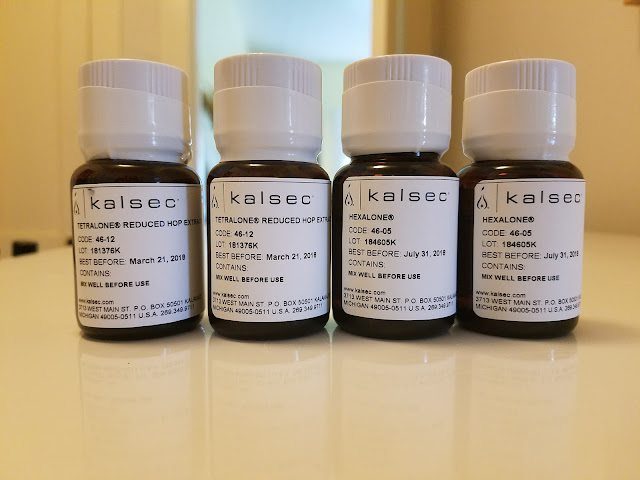

Fruit contributes simple sugars, which Lactobacillus love, and at the same time dilute the hop compounds in the beer. This can cause a precipitous pH drop. With so much beer already in barrels, my first maneuver was to begin dosing alpha acids into the beer along with fruit when there was already enough acid. We started with reduced iso-alpha-acids (e.g. tetralone/hexalone), but have moved onto Hopsteiner Alpha Extract 20% since it doesn't add perceived bitterness. About .1-.2 g per gallon stops acid production for our bacteria. These products don't significantly change the flavor or add additional aromatic complexity. As a side benefit, they enhance head retention. A small dry hop at this stage would be another option if you wanted stop acidification and add hop aromatics.

At this point we started upping the aged hop rate, or aiming for higher IBU targets when using fresh hops (~15-20 IBUs). At the same time (~2021) Scott and Ken (our head brewer) wanted to try barrel-aging more aromatically hoppy beers... I was resistant. I love hoppy-sour beers, I did a whole talk about them at the 2016 National Homebrewers Conference. Generally my approach had been to make sure the hops go into the beer as close to serving as possible (e.g., dry hop a barrel-aged sour after aging, brew a quick-turn hoppy Brett saison, add a whirlpool addition after kettle souring). I'd tasted too many barrel-soured IPAs and pale ales from great breweries that smelled like "old hoppy beer." That said, Ken and Scott convinced me! At our scale it is a relatively low risk to divert a few barrels of pale ale to see what happens.

We're already "aggressive" with our measures against oxygen pick-up (purging barrels with carbon dioxide before filling, purging the barrel-tool between each fill, purging the bottles before filling etc.), but when we fill barrels with pale ale wort we pull out all the tricks. Most importantly, we selected barrels that could be refilled without rinsing, leaving several gallons of "house culture" at the bottom of each. Our goal was to start the secondary fermentation as quickly as possible to protect the delicate hop compounds. I was amazed how good the resulting beer tasted!

What has really intrigued me is that the hoppier bases have almost universally produced finished beers I'd describe as more Brett-forward (earthy, funky, fruity, horse blanket). What I don't know is why! In American Sour Beers I cited research that Brett can free glycosides in hops, so that could explain the fruity. Maybe hops are just inhibiting Lactobacillus, giving the Brett a healthier environment (in lambics Brett tends to thrive before Pediococcus dramatically lowers the pH). Maybe I'm just being fooled and higher hopping rates (aged or fresh) are adding key compounds that I associate with the "funk" in a Cantillon, Orval (and many of my favorite American mixed-ferms)! These days our typical hopping rate is .5 lbs/bbl of aged hops at the start of the boil, and .5 lbs/bbl or fresh low alpha-acid hops in the whirlpool.

Barrels of Rings is one of the bottles included with the first shipment of the Sapwood Cellars Shipping Club. It started as Rings of Light, brewed summer 2022, racked into barrels after primary fermentation, but before dry hopping. After 10 months of aging, we transfer directly from the two wine barrels into our blending tank (purged with 5.5 pounds of our selected Citra Cryo already in there). We agitated/roused and allowed to settle for a couple days, dropping the hops. Then we primed with sugar and rehydrated wine yeast (as we do for most of our barrel-aged sours) and partially carbonated the beer. As with the barrel fill, we're relying on CO2 purging of the bottles and the rapid refermentation to scavenge oxygen and preserve hop aromatics.

Recipe: Barrels of Rings

OG: 1.063

65% Briess Brewer's 2-row

14% Great Western Malted White Wheat

13% Grain Millers Flaked Oats

8% Best Chit Malt

IBUs: 40

.5 lbs/bbl Meridian @ Whirlpool (212F)

1 lb/bbl New York Cascade @ Whirlpool (180F)

Bravo Salvo Hop Extract @ Whirlpool (180F)

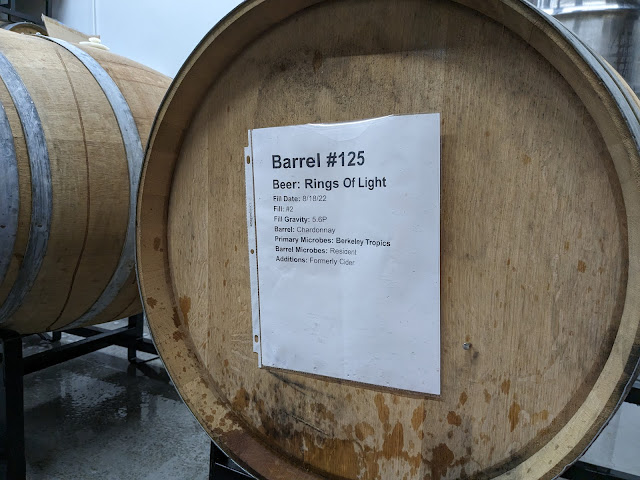

Fermentation with Omega Cosmic Punch (the barrel sheet below is incorrect)

FG (Primary) 1.022

Brewed 8/5/22. Barrels filled 8/11/22

Barrel #6: Fifth-fill Chambourcin red wine barrel that previously held our original barrel-aged pale ale, Measure Twice. That barrel was started with dregs from our collab with Free Will (Erma Extra), but along the way it was filled with bases that had dregs in primary from various American saisons (Casey and Holy Mountain).

Barrel #125: Second-fill Chardonnay white wine barrel that previously held a cider fermented with the Bootleg Biology Biology Mad Fermentationist Saison (plus we added the dregs from a stellar bottle of Barrique Wet Hop Reserve after filling).

6/21/23 116 gallons of beer from the two barrels transferred onto 5.5 pounds of 2022 Citra Cryo. 1.5 oz/gallon.

Carbonated to 2.05 vol, reyeasted with Premier Cuvee (rehydrated on a stir-plate with StartUp Nutrient), primed with enough glucose to add 1.1 vol of CO2 (~3.1 vol total in bottle).

Final pH: 3.65

Final Gravity 1.009

7.1% ABV.

Tasting Notes: Barrels of Rings

(My personal notes from a few months ago)

Smell - Nice blend of citrus (orange) and earthy-Bretty-funk. Still really fresh, no oxidative or old-hop aromatics. Really varied nose with a little pine sap, hay, and melon. Another hoppy base that got funkier than most of our bases.

Appearance - Big dense white head, good retention. Light haze, very pale yellow. Attractive.

Taste - Light lemony tartness, but not sour-sour. Very saison-y. Some bitterness, but it doesn’t clash with the light bitterness.

Mouthfeel - A touch of astringency. Great sptrizy carbonation. Medium-light body.

Drinkability - Really nice. The bitterness does give it a different impression than a classic low-bitterness sour base. More saison-like.

Changes for Next Time - Really good, not much to change on this one. Gin barrels would be fun.

When visiting Epochal Barrel Fermented Ales in Scotland last year I was blown-away by how by how good (owner/brewer) Gareth Young's wild ales were aged on whole hops in the barrels for the entire secondary fermentation. I really enjoyed the first beer we did with it, Violet You're Turning Violet (Mosaic in the barrel, finished with a blend of wild and cultivated blueberries). It seems like a good option especially if you want variety in the hop intensity of a base, e.g., start with a more moderate hopped base and add hops to some barrels for blending options.

France is famous for its attachment to good food and good alcohol—the French art de vivre. Beer still doesn’t seem to qualify as such. But that might be changing.

The post France Is Not a Beer Country, but It Could Be appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

In addition to music venues, bodacious barbecue, and epic tacos, this booming metropolis is The Lone Star State’s leading locale for incredible craft beer.

The post Three Beer-Filled Days in Austin, Texas appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Bière de garde is a malty style of beer that is undiscovered to many. Translated to "beer for keeping," the style was traditionally brewed in Northern France and is known for its malt-focused, toasty taste, and slight sweetness.

The post Bière de Garde: ‘A Breath of Fresh Air’ appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Smoothie sours are attracting a whole new audience of beer drinkers that otherwise would not make their way into a brewery.

The post Cheesecake and Ice Cream and Blueberry, Oh My: The Allure of Smoothie Sours appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

These five U.S. breweries all make good beer. But for folks who have been there, they know that they’re in for an experience that doesn’t stop there.

The post Five Unique Places to Drink a Beer appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

So why all of the excitement from our fellow craft brewers? Obviously many of the collab requests are due to Scott's writing about and advocacy for thiols, but are they just something new that will be passé soon, or are these strains here to stay?

Thiols are sulfur-containing compounds that are often potent aromatics. The ones brewers are excited about are tropical, winey, and citrusy, while other thiols are intensely unpleasant with aromas of garlic or rotten eggs... which is why the thiol mercaptan is added to natural gas to alert people to leaks. The "skunky" aroma of light-struck beer is also 3-methyl-2-butene-1-thiol.

Unlike many other beer aromatics that require concentrations in the ppm (parts per million) or ppb (parts per billion) many thiols have an aroma threshold in the range of 5-70 ppt (parts per trillion). This means that it doesn't take much of them to be apparent, but also means that it doesn't require "high" concentrations to become dominant.

In terms of positive beer and wine aromatics, the thiols that get the most attention are 4MMP, 3MH, 3MHA, and 3S4MP. These have perceptions that range from passionfruit, to grapefruit, to rhubarb. These are the intense aromatics that give New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc wines their distinct aromas and are found free at low-levels in many New Zealand hops (as well as some other varieties from around the world).

Most of the thiols found in hops, malt, and other botanicals are bound and thus not active aromatically. Enzymes are required to free them. There are wine strains available capable of this, but getting those genes into brewer's yeast requires more work.

Bound thiols are found in both malt and hops, but levels vary widely. The bond in need of breaking comes in two "flavors" Cysteinylated (Cys) and Glutathionylated (Glu). The vast majority (90%+) in both malt and hops is Glu. The IRC7 gene in certain wine strains and Omega's Cosmic Punch can only work on the less common Cys. As a result, mash hops are most potentially beneficial for Cosmic Punch, as the enzymes in the mash (especially in the acid-protein rest temperature range) can help convert Glu to Cys. Luckily some less expensive hop varieties have the highest levels of bound thiols. We've used Saaz, Cascade, and Calypso with good results.

The more intense strains like Berkeley Yeast Tropics line and Omega's Helio Gazer, Star Party, and Lunar Crush can simply be added to a standard recipe with or without whirlpool hops. Rather than having more copies of the IRC7 gene, they have a wholly different gene which can free Glu-thiols directly. The IRC7 gene in Cosmic Punch is "sourced" from yeast, while patB Omega uses in the more assertive strains is from a bacteria (if transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 gene modification is a step too far for you). We fermented a kettle sour which only had a small dose of hexalone (isomerized hop extract for head retention) with London Tropics. The result was intensely passion-fruity, so much so that it could almost pass a fruit beer.

GM (genetically modified) yeast strains aren't allowed in commercial beers in many countries (e.g., Canada, New Zealand). As a result there are labs working with wild isolates capable of freeing thiols for co-fermentations (e.g., CHR Hansen - it is primarily marketed for NA beers) and breeding strains with heightened thiol freeing capabilities (e.g., Escarpment). Omega initially worked on yeast breeding between English ale and a wine strain capable of freeing thiols... our trials with it (Designer Baby) were interesting, but had too much of the wine strain's idiosyncrasies present (poor flocculation especially).

Pros:

-Intense aromatics that are otherwise impossible to achieve from hops, malt, and yeast

-Thiols have incredibly low aroma thresholds... measured in ppt (parts per trillion)

-Thiols are "free" no expensive hops or fruit required

-Thiols may help increase shelf-life by scavenging oxygen

Cons:

-Higher perceived "sulfur" aromatics are frequent in thiol-freeing strains

-Some brewers/consumers/countries prefer to avoid GM ingredients

-Thiols can be "one note"... is it really that different from adding a jar of passion fruit extract?

-Repitching the yeast doesn't make as much sense if you also want to brew English Ales, Porters/Stouts etc.

Initially there was a focus on maximizing thiol concentration. This could include colder fermentation temperatures, mash hops, and engineering strains with more assertive genes. Like most aspects of brewing (or cooking) maximizing a single flavor compound doesn't usually result in the best overall flavor or balance.

Thiols aren't typically a "primary" aromatic in beer, so a beer with over-the-top thiol concentration without anything to play off of can taste artificial. On the other hand, some of our heavily dry hopped DIPAs have tested at over 100X the flavor threshold for 3MH and still weren't the primary aroma thanks to competition from the "traditional" hop aromatics. From those test, I wouldn't worry about dry hopping removing all of the thiols.

As a general rule, I'd suggest using a more restrained approach to thiols in lighter/cleaner/simpler beers. It doesn't take much to add a unique twist to a lager or American wheat, where a double-dry-hopped DIPA or fruit beer may benefit from a much higher amount. In the end it's about your palate and goals for a beer.

In my experience expressing thiols doesn't make every hoppy beer better. They add a distinct note that can greatly enhance the perception of passionfruit-type aromatics. That is a wonderful contribution when you are leaning into those flavors, but can be distracting or muddle other flavors. For example, I love the "mango popsicle" aroma of great Simcoe. However, with one of the intense strains like London Tropics or Helio Gazer in an all-Simcoe beer can become more generically "tropical" rather than varietal "mango." On the other hand, when dry hopping with passion-fruity Galaxy, or brewing with actual passionfruit the thiol note helps to enhance the existing aromatics.

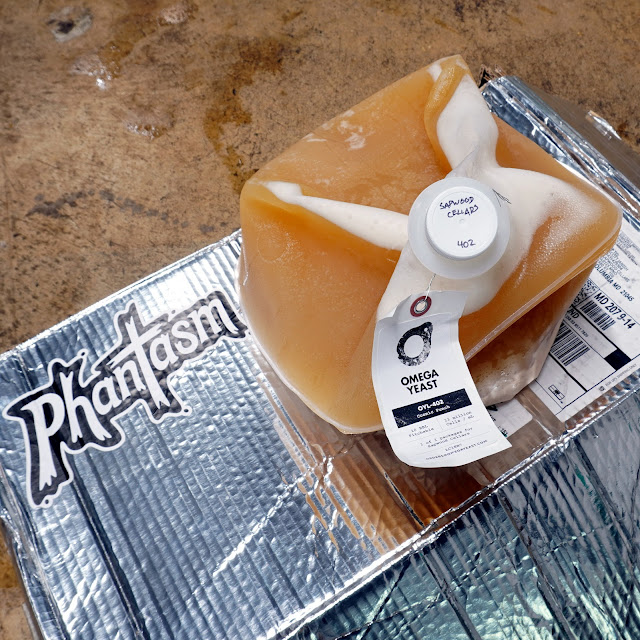

Hand-in-hand with thiol-expressing yeast goes Phantasm. It is essentially the dried and powdered remnants of the highest-thiol New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc grapes. As a result it comes with a high price-tag of ~$35/lb. It really doesn't smell like much before fermentation. Added to the whirlpool it adds a huge amount of bound thiols for the yeast to work on.

During fermentation I detect a distinct "white grape" flavor and aroma that I don't get from other thiol-expressing ferments that rely on grain and hops alone for bound precursors. A lot of this drops out with the yeast however and the finished beers are rarely as distinct. To my palate the added expense is hard to justify in a highly-dry-hopped beer where the thiols are competing against other big aromatics. Unless you lean into those aromatics with a hop like Nelson Sauvin. I like Phantasm best when it is paired with actual white wine grapes, or in a simple base where it can star.

We haven't used Berkely Yeast's "Thiol Boost" additive yet... but I'm just not that excited about a 15X increase on the already intense London Tropics level of 3MH. I'd be interested in herbs or additives that could push other unique thiol aromatics that we aren't getting from grain/hops.

At Sapwood Cellars, we've brewed a few dozen batches between Cosmic Punch, London Tropics, Lunar Crush, and experimental isolates. I've enjoyed most of them, but a handful stand-out as beers I loved!

Cosmic Rings: Galaxy and Citra is one of our favorite combinations... but we have had a difficult time sourcing great Galaxy (that doesn't taste like honey roasted peanuts). This all-Citra double-dry-hopped pale ale starts with New Zealand Taiheke (Cascade) in the mash and kettle. It's one of our favorite whirlpool hops because it is low alpha acid and has a beautiful tropical aroma... not to mention a lower price compared to other New Zealand varieties like Nelson Sauvin and Riwaka. Then we ferment with Omega's Cosmic Punch which brings some tropical aromatics without becoming distracting or artificial. Finally we dry hop with Citra and Citra Cryo at a combined 3 lbs/bbl.

Tropical Pop: Kettle sour fermented with Berkeley Yeast London Tropics along with passion fruit and mango purees. Passion fruit is expensive, fermenting with London Tropics boosted the passion fruit aroma allowing us to use less without sacrificing the aroma intensity.

Field Learning: As a homebrewer I loved being able to dump a bottle of thiol-rich New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc into a keg of mixed-ferm saison. That wouldn't be legal commercially, but what we did for this collab with Bissell Brothers was to brew a restrained base with Hallertau Blanc in the mash and Phantasm in the whirlpool and age it in fresh Sauvignon Blanc barrels along with Bissell's house culture. After a year we added fresh Chardonnay grapes from Crow Vineyards here in Maryland. The tropical notes from the thiols survived barrel aging and gave the beer depth we wouldn't have gotten from grapes and barrel alone.

Are thiols a scam? No, but they also aren't an innovation that fundamentally changes what it takes to make a delicious beer. Consider a thiol-freeing yeast when additional passionfruit-type aromatics will enhance your beer. Don't worry about maximizing the thiols unless you they will be competing against other strong aromatics.

I suspect that this is just the lead in to even more exotic genetically modified yeast strains (we have a pitch of Berkeley's Sunburst Chico which is modified to express high levels of pineapple-y ethyl butyrate). If you can produce a flavor compound without the cost, environmental impact, variability of growing it I suspect the economic pressures will be too great! That said, making delicious beers isn't about maximizing one or two compounds (in the same way that vanilla flavoring is inexpensive, but doesn't fully replace the depth and complexity of real vanilla beans).

Craft or not, our beer-drinking moms showed us from day one that beer isn’t just a man’s drink.

The post Cheers to Our Beer-Drinking Moms appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Jerry Franck, an Academy Award-nominated documentary filmmaker, followed a few notable lambic breweries to help sustain what many see as an anachronistic approach to beer making.

The post The Coolship Has Landed: Film Elevates the Art of Lambic Brewing appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

This week I take a closer look at the mashing process and what is actually going on when we mash malted barley and then sparge it to produce wort during the brewing process. The Purpose of Mashing Mashing is, in its most simple form, a process that breaks longer carbohydrate molecule chains into simpler sugars […]

This week I take a closer look at the mashing process and what is actually going on when we mash malted barley and then sparge it to produce wort during the brewing process. The Purpose of Mashing Mashing is, in its most simple form, a process that breaks longer carbohydrate molecule chains into simpler sugars […] (ST.LOUIS, MO) — Schlafly Beer, the original, independent craft brewery in St. Louis, announces the return of the popular seasonal beer, Raspberry Hefeweizen, a hazy, beer fermented with real fruit. At […]

The post Schlafly Beer Raspberry Hefeweizen Returns appeared first on The Full Pint - Craft Beer News.

Cocktail-inspired beers allow brewers to get more creative while providing craft beer lovers with even more variety and diversity.

The post Flavor Forward: Cocktail-Inspired Beers appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Dr Charlie Bamforth joins me this week to discuss health, wellness benefits and risks with beer. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does not support the audio element. Topics in This […]

Dr Charlie Bamforth joins me this week to discuss health, wellness benefits and risks with beer. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does not support the audio element. Topics in This […] Part of my routine is to scroll through Untappd to see if I can spot any common threads to the compliments or complaints... but I don't put a huge amount of stock in the average score (see this post). Blind rating by a skilled tasting panel is the gold standard... but having a large/diverse group of beer drinkers give you feedback has value as well! With four years of Untappd scores for our IPAs at my disposal, I thought it would be interesting to see which hops "the beer drinking public" preferred in Sapwood Cellars IPAs and DIPAs!

We started this series of IPAs when we opened to showcase our favorite hop varieties. We recently released #22 (Citra-Motueka). All of the batches were 6.5-7.5% ABV, with similar malt bills (American pale barley, chit, wheat, and oats), fermented with an English-leaning yeast, and dry-hopped post-crash at 3-4 lbs/bbl. The table below is the average Untappd score of all batches dry hopped with the variety listed.

The table below include all 65 "big batch" IPAs and DIPAs we've released that don't contain adjuncts (although I did include Phantasm beers). These are diverse in terms of recipe construction, alcohol strength, and dry hopping rate. As a result, the scores are a bit more prone to bias compared to the Cheater Hops data set.

For some batches you'd expect to see a high rating due to pairing two great hops together (e.g., Nelson/Galaxy or Mosaic/Citra). Both varieties score well across all our beers, so no surprise combing them results in a well-rated IPA. More interesting is sorting by the average standard deviation for the hops included. This shows which combinations rated higher than expected given the average scores for those hops across all beers. Snip Snap (Citra/Galaxy), Cheater Hops #22 (Citra/Motueka), Shard Blade (Mosaic/Galaxy), Cheater Hops #13 (Mosaic/Simcoe), and The Dragon (Nelson Sauvin/Mosaic/Hallertau Blanc) were all in the top-10 "overachievers." These hop blends follow different approaches either "leaning into" a particular flavor (fruity, or winey) or balancing fruity with a danker variety.

Rounding out the top-10 are two all-Simcoe (Cheater Hops #12 and Drenched in Green), two all-Mosaic (Fundle Bundle and TDH Trial #1), and an all-Nelson beer (3S4MP). Certainly a sign that these hops can shine alone compared to Citra and Motueka which are highly rated in blends, but haven't exceled in single-hop beers (despite our best efforts). Of course you need a great lot of hops for this to work; the bottom-10 also includes single-hop beers featuring: Simcoe (Cheater Hops #9), Nelson Sauvin (Cheater Hops #11), and Mosaic (Fumble Bumble)!

Two beers with Galaxy and Nelson (Cheater X and X2) each had a standard deviation close to 0. They still rate well, but no better or worse than expected across all beers with Nelson or Galaxy.

Surprisingly three of the bottom four included three varieties Cheater Hops #7 (Simcoe, Citra, Mosaic) Cheater Hops #6 (Motueka, Mosaic, Simcoe) False Peak (Idaho 7, Sultana, Citra). Blending hops can create a generic "hoppiness." These beers may have been missing a distinct "wow" aroma for people to grab onto.

The high/low scores for different batches brewed with the same single hop variety really drives home how unreliable this data likely is. Without multiple batches hopped with the same hop combination, it is impossible to say with certainty if a beer scored well because of aromatic synergy or a delicious lot of hops. Luckily several of the top-rated combinations are beers we have brewed multiple times.

The data does suggest to me that using one or two varieties for the dry hop is the best bet for making the most appealing IPA unless you have something very specific in mind. Often when breweries use a large number of hop varieties in a beer it is to promote consistency (batch-to-batch and year-to-year). It would be interesting to expand the data set to include beers from other breweries. That would produce data that is less specific to our particular brewing approach, hop sourcing, and customers' palates.