On their surfaces the fermentations of beer and wine seem like they should be similar. A cool, sugary liquid is inoculated with Saccharomyces cerevisiae (or a close relative) and the eventual product is packaged with a goal of minimizing oxidation. Why then are the two approached in such fundamentally different ways from yeast pitching rate to the use of oxygen scavengers?

I’ve only made a handful on wine kits over the years so I’m by no means an expert vintner. That said, I’ve been thinking about cider while I wait for TTB-approval to begin production at Sapwood Cellars. The question is, do we approach it like a beer or a wine?

Wine yeast has a different history than beer yeast. Where ale and lager strains have been domesticated for centuries, most wine strains were at best semi-domesticated until the last few decades. A big reason for that is the seasonal production differences between the two products. Dried grain and hops store and ship easily compared to grapes, so harvesting and repitching yeast was common in beer long before wine (which relied on an annual spontaneous fermentation).

Wine strains are still less domesticated (more wild) and thus tend to be more “competitive” than beer yeast, producing kill factors and generally being able to bootstrap up from low cell counts. As a result, suggested pitching rates for wine are usually much lower than for beer. A typical pitching rate for a 1.080 beer might be 3 grams of dried yeast per gallon, where wine is usually 1 g per gallon. This is also reflected in the package size for the strains (5 g vs. 11.5 g).

For home winemakers anyway, it is difficult to find best-practices for things like pitching rate and oxygenation. We can certainly debate the credibility and accuracy of the advice, but homebrewers have widely referenced formulas and targets for these based on original gravity and type of yeast (ale vs. lager).

Wine must isn't boiled to avoid destroying its fresh fruit flavor, so without chemical intervention there is no “clean slate” to begin fermentation. Even pitching a pure culture of yeast wouldn’t guarantee a product that doesn't eventually sour or go off. That helps to explain the common uses of antimicrobial sulfite and sorbate (which winemakers have widely referenced formulas for dosing rate). Chemical stabilization also allows the packaging of sweet wines, where brewers have mash temperature to control fermentability.

Most of the analysis of wine, must, and fermentation has happened since the 1970s. Where some of the earliest work on microbiology (not to mention scientific measurement) was from breweries a century earlier. Beer became science-ified first thanks to the earlier industrialization of brewing (again a result of the differences in ingredients).

Modern breweries are built upon keeping oxygen out of the beer post-fermentation. Much of this is accomplished with purging with carbon dioxide or nitrogen and transfers and packaging under pressure. Conversely, conventional wine production relies on dosing with metabisulfite (a potent oxygen scavenger) to neutralize oxidation while the process doesn’t do as much to avoid it.

Part of this is that breweries may make 25 or more batches of beer in a given fermenter each year, while seasonal wineries don’t have this luxury. This means even smaller breweries can afford to spend more on their equipment allowing for transfers under pressure rather than pumps. Dealing with force-carbonation makes pressure vessels a requirement. There are also stages of winemaking, like punch-downs or separating the skins from the fermented wine, that are nearly impossible to do without introducing some oxygen. There is also an expectation of stability and ageability with wine.

Traditionally beer was naturally carbonated, which allows the yeast to scavenge oxygen introduced during packaging. Combine that with typical quick consumption and oxidation wasn't as large of a concern until recently.

Natural wineries that avoid the addition of sulfites do take some cues from brewing in limiting oxygen, but this is currently a growing but still niche winemaking approach.

Beer has always been a recipe: grains, water, and herbs at a minimum. Sugars, fruit, spices etc. all have a historic precedent in brewing. It is no big surprise then that brewers are more likely to add 100 different ingredients than vintners who can make wine from crushed grapes alone - although adulteration had a historic place. Most of the wines I see with a "flavor" addition (e.g., chocolate, almond etc.) are inexpensive gimmicks. The lone exception is herbs in wines like vermouth. Where most of the expensive highly sought-after beers contain additions that fall outside of the core ingredients.

Modern wineries add all sorts of processing aids, acid/sugar adjustments, nutrients etc. but generally with the goal of balancing, showcasing, or heightening the fruit expression. Wine strains are now carefully selected to have specific interactions to increase aromatic compounds (e.g., the ability to converts the thiol 3MH to 3MHA). Wine yeast blends are also popular with one strain freeing a compound and another converting it. All things that are rarely considered for brewing.

Brewers have only relatively recently begun to embrace aging in oak barrels, something many wineries never gave up on when stainless steel became the standard. Brewers have very much relied on the secondhand barrels from wine and spirit production rather than buying new or directly supporting coopers.

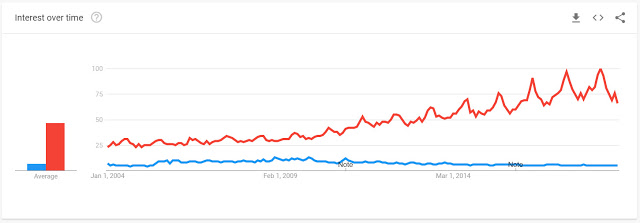

This goes after the larger point that brewers are currently less tethered to their industry's recent past than wineries. The most popular craft beers of today don't look or smell like any beers that were produced 30 years ago, while wines have remained relatively unchanged. Much of the American craft beer boom was based on taking dead or dying styles, ingredients, and techniques and resurrecting them. It is great to see the same becoming more popular in wine with the resurgence of orange wine, obscure varietals, and natural winemaking.

I’m not here to argue that either brewers or vintners are better. I think there are things that each side could learn from the other. Why don’t we see dry hopped wine? Why don’t brewers add 5 PPM of metabisulfite as insurance for the hazy IPAs? Why don’t we see more wineries reduce their sulfite usage by purging their tanks and bottles? Why don’t we see more brewers celebrate the terroir of local ingredients? I even wrote an article for BYO about using wine yeast in beer.

Someone could likely write a similar article about distilleries, cideries, sake-producers, etc. The point is to get out of your box, and see what other experts suggest in their chosen domain. Determine if any of it is useful to what you do!

I've talked to cidermakers who operate just like a winery in terms of their fermentation and highlighting of the apples, while others are clearly more influenced by craft beer (take Graft). We'll likely take a hybrid approach for our ciders, using our best low-oxygen transfers along with winemaking techniques that make sense to us. Celebrating the character of the apples, but still sometimes having fun with additional flavors.

I’ve only made a handful on wine kits over the years so I’m by no means an expert vintner. That said, I’ve been thinking about cider while I wait for TTB-approval to begin production at Sapwood Cellars. The question is, do we approach it like a beer or a wine?

Wine yeast has a different history than beer yeast. Where ale and lager strains have been domesticated for centuries, most wine strains were at best semi-domesticated until the last few decades. A big reason for that is the seasonal production differences between the two products. Dried grain and hops store and ship easily compared to grapes, so harvesting and repitching yeast was common in beer long before wine (which relied on an annual spontaneous fermentation).

Wine strains are still less domesticated (more wild) and thus tend to be more “competitive” than beer yeast, producing kill factors and generally being able to bootstrap up from low cell counts. As a result, suggested pitching rates for wine are usually much lower than for beer. A typical pitching rate for a 1.080 beer might be 3 grams of dried yeast per gallon, where wine is usually 1 g per gallon. This is also reflected in the package size for the strains (5 g vs. 11.5 g).

For home winemakers anyway, it is difficult to find best-practices for things like pitching rate and oxygenation. We can certainly debate the credibility and accuracy of the advice, but homebrewers have widely referenced formulas and targets for these based on original gravity and type of yeast (ale vs. lager).

Wine must isn't boiled to avoid destroying its fresh fruit flavor, so without chemical intervention there is no “clean slate” to begin fermentation. Even pitching a pure culture of yeast wouldn’t guarantee a product that doesn't eventually sour or go off. That helps to explain the common uses of antimicrobial sulfite and sorbate (which winemakers have widely referenced formulas for dosing rate). Chemical stabilization also allows the packaging of sweet wines, where brewers have mash temperature to control fermentability.

Most of the analysis of wine, must, and fermentation has happened since the 1970s. Where some of the earliest work on microbiology (not to mention scientific measurement) was from breweries a century earlier. Beer became science-ified first thanks to the earlier industrialization of brewing (again a result of the differences in ingredients).

Modern breweries are built upon keeping oxygen out of the beer post-fermentation. Much of this is accomplished with purging with carbon dioxide or nitrogen and transfers and packaging under pressure. Conversely, conventional wine production relies on dosing with metabisulfite (a potent oxygen scavenger) to neutralize oxidation while the process doesn’t do as much to avoid it.

Part of this is that breweries may make 25 or more batches of beer in a given fermenter each year, while seasonal wineries don’t have this luxury. This means even smaller breweries can afford to spend more on their equipment allowing for transfers under pressure rather than pumps. Dealing with force-carbonation makes pressure vessels a requirement. There are also stages of winemaking, like punch-downs or separating the skins from the fermented wine, that are nearly impossible to do without introducing some oxygen. There is also an expectation of stability and ageability with wine.

Traditionally beer was naturally carbonated, which allows the yeast to scavenge oxygen introduced during packaging. Combine that with typical quick consumption and oxidation wasn't as large of a concern until recently.

Natural wineries that avoid the addition of sulfites do take some cues from brewing in limiting oxygen, but this is currently a growing but still niche winemaking approach.

Beer has always been a recipe: grains, water, and herbs at a minimum. Sugars, fruit, spices etc. all have a historic precedent in brewing. It is no big surprise then that brewers are more likely to add 100 different ingredients than vintners who can make wine from crushed grapes alone - although adulteration had a historic place. Most of the wines I see with a "flavor" addition (e.g., chocolate, almond etc.) are inexpensive gimmicks. The lone exception is herbs in wines like vermouth. Where most of the expensive highly sought-after beers contain additions that fall outside of the core ingredients.

Modern wineries add all sorts of processing aids, acid/sugar adjustments, nutrients etc. but generally with the goal of balancing, showcasing, or heightening the fruit expression. Wine strains are now carefully selected to have specific interactions to increase aromatic compounds (e.g., the ability to converts the thiol 3MH to 3MHA). Wine yeast blends are also popular with one strain freeing a compound and another converting it. All things that are rarely considered for brewing.

Brewers have only relatively recently begun to embrace aging in oak barrels, something many wineries never gave up on when stainless steel became the standard. Brewers have very much relied on the secondhand barrels from wine and spirit production rather than buying new or directly supporting coopers.

This goes after the larger point that brewers are currently less tethered to their industry's recent past than wineries. The most popular craft beers of today don't look or smell like any beers that were produced 30 years ago, while wines have remained relatively unchanged. Much of the American craft beer boom was based on taking dead or dying styles, ingredients, and techniques and resurrecting them. It is great to see the same becoming more popular in wine with the resurgence of orange wine, obscure varietals, and natural winemaking.

I’m not here to argue that either brewers or vintners are better. I think there are things that each side could learn from the other. Why don’t we see dry hopped wine? Why don’t brewers add 5 PPM of metabisulfite as insurance for the hazy IPAs? Why don’t we see more wineries reduce their sulfite usage by purging their tanks and bottles? Why don’t we see more brewers celebrate the terroir of local ingredients? I even wrote an article for BYO about using wine yeast in beer.

Someone could likely write a similar article about distilleries, cideries, sake-producers, etc. The point is to get out of your box, and see what other experts suggest in their chosen domain. Determine if any of it is useful to what you do!

I've talked to cidermakers who operate just like a winery in terms of their fermentation and highlighting of the apples, while others are clearly more influenced by craft beer (take Graft). We'll likely take a hybrid approach for our ciders, using our best low-oxygen transfers along with winemaking techniques that make sense to us. Celebrating the character of the apples, but still sometimes having fun with additional flavors.