The Brewers Association and CraftBeer.com are proud to support content that fosters a more diverse and inclusive craft beer community. This post was selected by the North American Guild of Beer Writers as part of its Diversity in Beer Writing Grant series. It receives additional support through a grant from the Brewers Association’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee and Allagash Brewing Company.

To get to know a city’s beer scene, it’s important to know more than what’s in your glass. You also need to know the history. Walking to breweries lets you appreciate aspects of a city you may not notice buzzing by in a car, so I traveled to Grand Rapids, Mich. to explore what USA Today has called “Beer City USA.” You can visit 25 breweries and trek 100 miles—all without getting in a car. But the beer isn’t the only thing that captures attention.

A mid-sized city of 200,000 people, Grand Rapids is the second most populous city in Michigan after Detroit. Grand Rapids is 65.5% non-Hispanic white, 18.1% Black, and 16.3% Hispanic—more diverse than Michigan as a state.

In 2015 Forbes ranked it the second-worst U.S. city for African Americans to live based on metrics such as entrepreneurship and homeownership. In May, the police shooting of a Black man sparked debates on race relations in the city. Yet the stories I heard from residents reveal more than what statistics offer.

‘Underserved and Ignored’

Tucked near the interchange of I-196 and US-131, New Holland’s Knickerbocker is the Grand Rapids outpost of Michigan’s largest independent brewery. I fantasized about spending time in the airy multi-floor taproom here on days too cold to play outside.

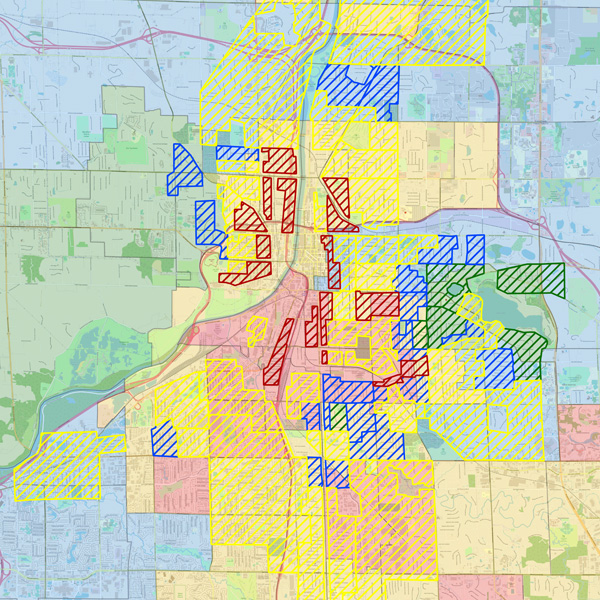

Although redlining ended in the 1960s, its repercussions linger. Zillow and Redfin report that real estate values in redlined areas across the country can be 10 times lower than in non-redlined areas.

Doug Hoverson, a historian working on a book about Michigan breweries, said that in the 1980s and 1990s, not unlike today, breweries formed in “the cheapest industrial building they could find with a drain.”

Cross-referencing the 17 breweries within city limits with a 1940s map, I find two other breweries in the same redlined neighborhood as The Knickerbocker. Jolly Pumpkin Artisan Ales is across the street. Arvon Brewing and Speciation Artisan Ales are in redlined neighborhoods east of the river. That’s a disproportionate number of breweries on the 6% of the city’s land deemed “hazardous.”

When Speciation Ale’s Mitch Ermatinger moved to the area as a resident in 2008, he was unfamiliar with the history, but fell in love with its progressive culture. Still, he recognized that “many parts of Grand Rapids are still underserved and ignored.” When the brewery relocated in 2019, the choice of community was “100% intentional.” In its former industrial location, Speciation had mainly attracted white men. For the brewery’s new taproom, he wanted something different.

How Redlining Impacted Beer Drinking

Even though descendants of redlined residents live near and drink at Grand Rapids taprooms, they still aren’t the owners of the breweries. Black Calder Brewing, founded by Grand Rapids native Terry Rostic and Michigan native Jamaal Ewing, is one of just two Black-owned breweries in the state.

“I went to different breweries in the area and I never saw anyone like me. I was always the outsider,” Rostic said. With Black Calder, he and Ewing are challenging that narrative.

In a city saturated with breweries, Black Calder faces unique challenges. Though established in 2020, it is still looking for a brick-and-mortar taproom.

“How property was divided and shifted within Grand Rapids impacts how we operate and try to find a location today,” Rostic said. “A lot of property [in Grand Rapids], at least commercial property, is not owned by African Americans.” For now, Black Calder releases beer through collaborations with Speciation Artisan Ales and other breweries.

A history of redlining impacts fundraising, too: A quarter of new businesses rely on family money to start, and women and minorities are disproportionately impacted by systemic issues that hindered generational wealth. “I have buddies who started breweries and were able to draw hundreds of thousands of dollars from family,” Rostic said.

“Home values in the neighborhoods where my grandparents weren’t allowed to live were maybe $10,000 in the 1970s and now [they’re] worth $600,000,” Rostic said. “Where my grandparents were able to buy a house, overpay for that house, get very high interest loans, finally pay it off—it’s still in a place where their home values are not a quarter of others in the city.”

In Grand Rapids, highway construction for I-196 and US-131 uprooted 4,000 Black families. Those displaced moved in with relatives or rented, which reduced intergenerational wealth. That scenario impacts traditional bank financing, too. Nationwide, inequality in homeownership has contributed to Black Americans holding only 10% of the assets of white Americans.

Without home equity, entrepreneurs can’t come up with collateral. “Since we didn’t have these opportunities, redlining absolutely makes an impact today on business and entrepreneurship in Grand Rapids,” Rostic said.

While all breweries need financing, it’s harder for entrepreneurs of color.

The Federal Reserve reports Black and Hispanic-owned businesses face disparity in funding. “These things are amplified 100 times in the craft beer industry because of all the regulations, no matter what you look like,” Rostic said. “When you add in generational and historical impacts, there’s no reason not to understand why in Grand Rapids, Mich. you’ve never had a Black-owned brewery until 2020. These are all by design.”

In a brewery-dense city, the two-mile walk across southeast Grand Rapids was my longest stretch between taprooms. If I had been in a car, the trek from Brass Ring Brewing to ELK Brewing would have gone by in a blink. On foot, it’s easy to see these neighborhoods have the highest density of Black and Hispanic people.

That’s why Rostic wants Grand Rapids’ 49507 ZIP code to be the future home of Black Calder, “to show minority entrepreneurship—someone from this area—can be a catalyst, the building that invites other businesses to come.”

Funding Diverse Beer

From the city center, I head north on the bike trail for half a mile to City Built Brewing, on the east bank of the Grand River. City Built is the only Hispanic-owned brewery in Grand Rapids. Owner Edwin Collazo’s parents are from Puerto Rico. The brewery reflects his culture in the menu and beer names, like Hola, Mi Nombre Es, a fruited lactose sour.

Before starting City Built, Collazo was a financial planner with a 15-year homebrew hobby. He started getting serious after joining an online national beer exchange group. “I guess they needed someone who could get Michigan beers,” he jokes.

While he wasn’t seeing local beer enthusiasts who looked like him, he found others online “who were leaders, decision makers at different breweries who had developed clout or respect for their skill set.” Collazo saw what could be possible in Michigan. “If you go to places where lots of minorities live, they like good beer. It’s working because of their decision makers—they’re marketing to other brown people.”

When it came time to raise money, networking skills from his prior job were a bonus. Collazo pitched City Built as a culturally diverse business that would add something unique to the city. “We did that, because 10 years ago, I don’t think Grand Rapids was ready, where now it’s almost cool and in vogue to seek out a cultural experience,” he said.

Still, convincing investors was a challenge. “When we talk about a guy who looks like me, trying to open a business in this town, it’s really hard to get past the old guard,” Collazo said. As a financial adviser, he’d seen the advantages that come to “blond, blue-eyed guys.”

“I had a white counterpart and he was seen as the credibility. I was referred to as ‘that brown guy who spoke well,’ which is funny for a guy from Ohio,” Collazo said.” He jokes, but Collazo and his parents were born in the U.S. and he has two degrees from American universities.

As with Black Calder, Collazo sees City Built as a conduit to serve his community and “give Hispanic people an upscale place where they can find familiar food and familiar flavor.”

On my brewery walk, taproom staff often recommended competitors’ beers to me. Collazo says other breweries tell tourists, “‘If you go to one more place [in town], you have to go to City Built.’ I think that happens because it’s so different. You can’t find this anywhere else.”

Education Can Change Who Brews

Hidden in the Applied Technology Center at Grand Rapids Community College (GRCC), Fountain Hill Brewery is the public-serving side of the school’s craft beer program.

Molly Daniels, an adjunct professor in the craft brewing program, said that knowing beer production science is the gateway to the changing beer industry: “If you can have a conversation about beer and brewing, that opens the door to so many things.”

Daniels is a graduate of the program herself. Now she’s a brewer at Railtown Brewing, in the greater metro area.

A full-time student can achieve a certificate in a year, though most students take two years to work part-time in the industry. The program, which has been around since 2016, expects 18 students next fall.

Allison Hoekstra, a professor who teaches beer sensory classes, said that a majority of graduates end up working in beer across a variety of jobs.

While GRCC’s program has yet to attract many people of color, it has provided a path for female brewers. Daniels was one of the first two women to receive a certificate in brewing. Now, 20% of her students are women, compared to 7.5% of working brewers nationwide.

Hoekstra, who also is on the education committee at Grand Rapids’ Beer City Brewers Guild, said that costs can be a barrier to learning. That’s one reason Rostic wants to develop a GRCC Black Brewer’s scholarship, in the footsteps of similar programs elsewhere in the country.

Stepping Up to the Challenge

“People are starting to see that inclusion is real,” Rostic said. “Some people do it because it makes business sense. Some people do it because they want more people to drink good beer.”

How can the industry use its resources to support nontraditional brewers?

Rostic references the difference between equity and equality. “I don’t want a handout. I want an opportunity. I want to compete.” He recognizes that redlining harmed intergenerational wealth in Grand Rapids. That’s why for him, equity looks like financing: “Low interest loans, banks not asking for so much collateral.”

There’s a precedent for the beer community providing access to capital. A program run by Sam Adams and the Accion Opportunity Fund provides loans and business mentoring for women and BIPOC.

“If you want to diversify, you want to be inclusive, you recognize things haven’t been right, you’re going to have to do things that you’ve never done before,” Rostic said.

As I walk through Grand Rapids, I imagine what it would be like if seven of Grand Rapids 40 breweries were Black-owned and six were Hispanic-owned, reflecting demographics.

Rostic says that won’t happen without dedication. “We really need a heart-to-heart and some soul searching as a community of business leaders, banks, and institutions to say, ‘If we want to make this happen, then we’re going to help you by any means necessary.’ That’s what’s needed in Michigan and everywhere across the country.”

The post A Walk through History and Race in Beer City USA appeared first on CraftBeer.com.